How to Start With Static Sites

29 Nov

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat are they and all the things you need to start one of your own

For most newcomers to web development, dynamic websites are the standard in Web 2.0 interactions. But that was not always the case.

The move to dynamic sites

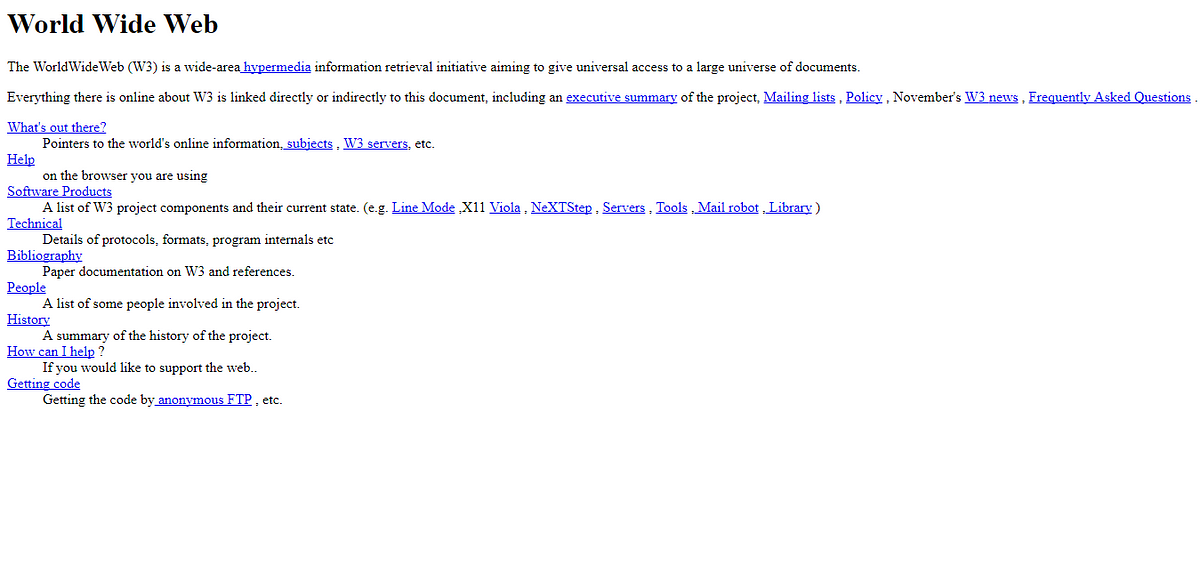

When Tim Berners-Lee created the internet, as an information-sharing portal between scientists, web pages were static HTML documents.

Websites, at the time, were a collection of these static documents, stored in their entirety and there was minimal interface on the server-side.

With the introduction of CGI or Common Gateway Interface, this changed. CGI allowed websites to run scripts and this enabled the webserver to be more than just a storage facility of static HTML documents. The output of the scripts could be run on the server and displayed back on the website.

This led to dynamic websites — websites with which you could interact and communicate. Along came a host of server-side technologies and websites become more like applications being served on the webserver.

Why use static sites

However, when it comes to aspects like speed, reliability, and scaling, static sites offer unmatched performance. For use cases where content does not change often, such as blogs, landing pages, documentation, and portfolio sites, static sites are a great solution.

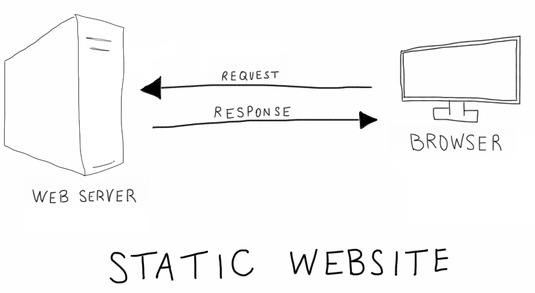

A static website is delivered to the user exactly as it is stored on the web server.

This is because static sites are stored entirely in the server and only have static HTML, CSS and JavaScript files in them. When the server has to render the static site, it is able to serve the collection of files without having to send additional queries to a back end database. Each time an edit is made to the site’s content, it can be updated on the server end, in the static files. Since it is the browser that interprets HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, and not the server, this enables a much more secure data package to be delivered and reduces the chances of a site failure.

The most common challenges are:

- Deploying a static site has a steeper technical curve than publishing via a content management system like WordPress, Drupal, or Django.

- There are limitations to what can be offered on the client-side. For example, for an eCommerce site, the static route would not be a great idea. Similarly, for monetizing web pages using targeted marketing ads, static sites would be a dead-end (though you can always put banner ads on a static site).

The former is a speed bump, but tools like Lektor and Publii (more on them below) are making it easier to lower the barrier of entry. Jekyll, one of the most popular static site generators, is also growing in adoption.

Static progressive web apps are now coming to the fore. These enable a lot of client-side interaction using JavaScript and its frameworks, which may have been limited to dynamic sites earlier. For example, check out Balsamiq’s contact us page, here. It is a static page using React.

This article compiles a list of the resources you need to serve up your very own static site.

Note: If you have no previous experience with a static site before this, no worries. This article covers static site generators and CMSs that can help in that. I’d really advocate the “seeing-is-believing” approach when it comes to appreciating the performance of a static site. So just go ahead and jump into static sites with one of these tools.

Static Site Generators

One of the essential characteristics of a static site generator is that it serves up a simple source folder, which is a self-contained static website in itself. Hosting this folder on the server will deploy the static site. Here is an exhaustive list of options when it comes to static site generators.

1. Jekyll

One of the most popular static site generators, it supports importing from many dynamic blogs. It’s written in Ruby and is the engine behind GitHub Pages.

2. Hexo

Written in JavaScript and powered by Node.js. It allows one command deployment to GitHub Pages, Heroku, OpenShift, etc.

3. Metalsmith

Simple and extremely pluggable static site generator — apart from the core functionality, everything is handled by plugins so it is extremely flexible. It’s written in JavaScript and can be used as more than just a static site generator; whether as a build tool or even a documentation generator.

4. Hugo

Extremely fast and flexible. It’s written in Go. It comes with a bare bone structure in place so that you customize it down to the smallest detail.

5. Pelican

Written in Python, Pelican can handle content input in multiple formats (Markdown, reStructuredText, etc.). It also provides multilingual support beyond English.

6. GatsbyJS

Written in JavaScript, it generates a Static Progressive Web App; one advantage being that every change made can almost immediately be seen without having to reload the web page every time. It’s powered by React.js.

7. Wintersmith

Written in CoffeeScript and built on Node.js. It’s minimalistic, but can be customized and scaled with plugins.

8. Nuxt

Nuxt creates a static generated Vue.js application. It’s written in JavaScript and uses Vue SSR to generate client as well as server-side pages.

9. Middleman

Written in Ruby. Ruby language and RubyGems need to be installed to run Middleman. Minification, compressions, and cache-busting are built-in. It follows Ruby on Rails conventions.

10. Assemble

Written in JavaScript and built on Node.js. It has a host of plugins available; lots of options to customize.

11. Octopress

Built on top of the Jekyll framework, the difference is that it does away with the time-consuming parts of setting up a Jekyll site-like configuration. It’s written in Ruby. The latest version, Octopress 3.0, restructures the framework so that each feature becomes an extensible gem with its own documentation. This way users can customize and choose the parts of Octopress that they want to implement on top of Jekyll.

12. Hakyll

Written in the Haskell language. It is well suited to small and medium sites.

13. Sculpin

Written in PHP and with a very simple setup. It combines plain text files with Twig templates to generate static pages.

14. Gutenberg

Written in Rust, which gives it great compilation speed. It comes as a single executable file with no dependencies. Gutenberg also has Sass compilation and syntax highlighting built-in.

15. Jigsaw

Written in PHP. Jigsaw compiles assets using Laravel Elixir. Elixir can be pre-configured so that the site is rebuilt automatically every time a change is deployed.

16. Statik

Written in Python. It provides a fully customizable data model the ability to define custom taxonomies. It is good for creating static sites beyond blogs.

17. MkDocs

Written in Python. MkDocs is aimed at creating quick project documentation with Markdown. It allows previews as you build and can be hosted almost anywhere.

18. Cactus

Written in Python. Cactus is easy to develop locally and deploy directly to Amazon S3. It has the option to preview the site from the development web-server built-in.

19. DocPad

Written in CoffeeScript. DocPad is a dynamic static site generator; this means that it takes content from several sources and renders them as a static output. It has a tiny core with non-essential functionality offered as plugins, which means it’s lean and extensible.

20. Phenomic

Written in JavaScript. Phenomic uses the React framework, which renders both client and server-side pages. The user sees a static-pre-rendered version of the site, and as they explore new pages only the data necessary to render those parts is served. It is now pivoting towards being a modular website compiler so the static site can be rendered not just in React, but also in ReasonReact, Preact, Next.js, Vue, and Angular.

21. React-Static

Written in JavaScript and focused on site performance, SEO, and user/developer experience. It renders the site a progressive static application.

22. Harp

Written in JavaScript, Harp comes with built-in preprocessing. It compiles a project down to its basic static assets.

23. Expose

Static site generator that turns folders of images and videos into photo essays. It runs as a bash script and requires Imagmagik and FFmeg to work. Ideal for users who need a photo portfolio or gallery. This is a great example of what can be done with Expose.

24. Roots

Written in CoffeeScript. Good for building static front ends, especially small to medium-sized.

25. Nikola

Written in Python. It provides incremental builds and supports multiple input formats — reStructuredText, Markdown, IPython Notebooks, and HTML.

26. Punch

Written in JavaScript, Punch is a web publishing framework built for designers and developers. It has a quick setup thanks to boilerplate code and minimal templates thanks to Mustache.

Static Content Management Systems

You may ask why do I need a CMS if I’m using a static website? Well, the one thing that CMSs do simplify is access for non-technical users and enabling that content bottlenecks do not occur because of just one pipeline to push content. The issue with a lot of static site generators is that there is a fair amount of technology deployment. These CMSs can help with that.

1. Netlify CMS

Open source; Works with most static site generators; Git-based.

2. Forestry.io

Free personal plan, paid plans starting from $9/site/mo; Supports Jekyll and Hugo; Git-based.

3. Siteleaf

Free developer plan, paid plans starting from $7.20/mo; Supports Jekyll; Git-based.

4. DatoCMS

Free developer plan, paid plans starting from €9/mo (discounts for more than 1 site); Supports — Jekyll, Hugo, Middleman, Metalsmith, GatsbyJS, Hexo; API-based.

5. Publii

Open source; Publishes websites as static HTML files; App-based.

6. Sitecake

Open source; Drag and drop editor for HTML and PHP websites.

7. CloudCannon

Free starter plan, paid plans start from $25/mo; Supports Jekyll; Git-based.

8. Lektor

Open source; Publishes sites as static HTML files; App and API-based.

9. Appernetic

Free plan till 14 publishings per week, Paid plans start from $0.5–$20.5; Supports Hugo; Git-based.

10. Bowtie

Plans starting at $10/mo; Supports Jekyll by default but can support other static site generators; Git-based.

11. Contentful

Free developer edition, paid plans starting at $249/mo; Supports Middleman, Jekyll, Metalsmith; API-based.

A static site can load up to 6 times faster than a regular web page! Considering such numbers and the effects that can have not just on user experience but also on the Google ranking and SEO, static sites are surely an area worth considering for your own website.

If you’re looking to build your own site then this article may also be helpful:

How Do I Make My Own Website?

Request Demo

Request a personalized demo of zipBoard to annotate, comment, share feedback, and track changes on your web project or mocks — all in one place.

Get DemoRelated Post

Recent Posts

- User-Friendly E-Learning Review Tools: Trends for Teams in 2026 February 20, 2026

- Your Digital Asset Review Workflow Is Broken (And How to Fix It) February 3, 2026

- Best Practices for Efficient Document Reviews and Collaboration December 18, 2025

- MEP Document Management: How to Streamline Reviews & Avoid Rework October 3, 2025

- What Is Online Proofing Software? And Why Content Review Breaks Without It July 11, 2025

©️ Copyright 2025 zipBoard Tech. All rights reserved.